SCENE 1. EXTERIOR DAY; MORNING (AUTUMN 791); THE MARKETPLACE, A SMALL VILLAGE NEAR YORK, ENGLAND.

Amid the turmoil of tumblers and jugglers, a conjurer swallowing fire and a bear dancing miserably at his master's bidding, a small girl of about seven years is running circles around her father, who is staggering beneath the enormous bundle on his back. Both of them are dressed in coarse, soiled clothing and their faces and arms are covered with grime. But even through all the dirt it is obvious that the girl has especially fine features and thick, blonde hair. She runs gracefully from stall to stall admiring the delicacies of honey, salt, oil, butter, fruit, wine, and fine silksÑall the while balancing a basket of goat cheese on her head. She gapes at the stalls displaying peacock feathers and pet monkeys, but manages to keep in step with her father through all the chaos. Then her eye is caught by a bolt of magnificent red cloth being swept into the air by a merchant on the other side of the muddy road. As she makes a quick leap in front of her father, the corner of her basket catches on his bag, the small round cheeses tumble into the gutter and are carried away in the muddy water.

JOAN'S FATHER Cursed girl-child! Upon my oath, you were born under the devil's own star!

The girl is leaning over the gutter trying to rescue some of the cheese as a fat white pig gobbles them up. Her father throws down his load, grabs her by her long dirty hair, slaps her full in theface and tosses her back down into the muddy gutter.

JOAN'S FATHER That'll teach you to throw my cheese to pigs! He gives her a last look of disgust, picks up his load and continues through the crowd. A young monk who has been reading under a tree comes running to the scene and tries to grab hold of the pig. He is dressed in the white robe of a Benedictine novice and is quickly splashed with mud. YOUNG MONK Toto! Stop! In the name of St. Mary, stop! The monk tries to grab hold of the slippery pig and ends up in the mud next to Joan. Her tears disappear and a smile appears on her

face as she watches the monk in his white robe wrestle with the pig in the mud. She captures a piece of cheese and jumps up, running toward the tree where the monk had been seated.

JOAN Here Toto!

Pretty Toto! Slippery little pig! The pig obediently follows her to the tree, where she gently feeds it the cheese.

YOUNG MONK (confusedly) Toto. . . The cheese! . . . Are you hurt? . . . Poor child. . . God forgive me, but that man is a brute and now he has abandoned you midst ruffians and strangers.

JOAN (still stroking the pig) Oh, finding him will be no problem. He'll be at the Boar's Head Inn when the sun reaches heaven.

YOUNG MONK And when in God's good name be that?

JOAN When everyone goes in to eat and even shadows hide.

YOUNG MONK And you, you eat in the devil's church with thieves and loose women?

JOAN No. I wait outside till the business is done. Most times I get a sweetmeat and a cup of cow's milk, but not today. I've lost his cheese. The best of the season. He planned to trade it towards a harness for the ox.

YOUNG MONK And if he has an ox, why carry the burden on his back? JOAN To save the tax. You needn't pay for what you carry on your back. Did youcarry the pig?

YOUNG MONK No. Monks have a dispensation.

JOAN Dispen...?

YOUNG MONK Dis-pen-sa-tion. We pay no market tax.

JOAN Is it written in your book?

YOUNG MONK No. It's book of gospel my guide to wisdom and holiness.

JOAN And would it be wisdom to sell your pig? My father would trade you his sack of rye. He promised that one fine day we would eat white bread and roast pig like the duke himself. Perhaps it is a fine day, in spite of the cheese.

YOUNG MONK (looking shocked) Toto? Roasted? No. Never. She's my pet. My companion through thick and thin. The young monk grabs his pig from Joan and heads toward the road, turning back as an afterthought.

YOUNG MONK I'll pay you back the cheese, of course. The feast of St. Denis. High mass at the cathedral. You'll be there? Joannods her head slowly in agreement. The monk disappears rapidly in the crowd as they laugh at his muddied white robe and squealing pig. Joan plops sadly down by the tree, then her face lights up. Next to her is the monk's forgotten book. She picks it up and rushes after him, but he is nowhere to be seen. Smiling, she wraps it in her white cheese cloth, hides it under the straw of her nearly empty basket, and lets herself join in the flow of merrymaking.

2. INT. DAY;LATE AFTERNOON, THE HAYLOFT OF A RICKETY BARN.

Joan is kneeling in front of a bale of hay with a burlap bag covering her head and shoulders in imitation of the young monk's robe. She has spread her white cheese cloth on the bale of hay as if it were an altar cloth. On it lays a large leather-covered book. The scene is lit by white rays of sun that filter through the dilapidated roof and fall on Joan's face and on the book. She slowly opens the book and we see a beautifully illuminated manuscript from the Gospels of St. Mark which depicts the visit of the Magi at the Nativity. Joan pretends to read the text:

JOAN And the barefooted kings, queens, knights, monks, thieves and loose women, ruffians, strangers, horses, dogs, cats, and pigs came to kiss the new-born baby who was God. They had all followed the good star under which the baby was born and all covered their faces to not be seen by the devil's own star from which all evil children do appear. And one young handsome monk appeared all sparkling in a robe of white and he did say in dis-pen-sa-tion, "I give to you Toto, my pet and my companion through thick and thin." And the baby did smile and St. Joseph roasted the pig for dinner that the baby God should eat like a King. Amen The calm, religious spell is broken by the sudden opening of the barn door below. The atmosphere is overwhelmed with harsh dirty light, and the clamor of goats being forced through the opening by barking dogs. Joan quickly closes her book, wraps it in the white cloth, and hides it in the hay. She then rushes down the ladder and nearly collides with her mother who has placed a crying baby in a makeshift crib, closed the heavy barn door, grabbed a stool

and is already busy milking an uncooperative goat. Like the rest of the family Joan's mother is bedraggled and dirty, but she is also bent over by years of hard work in the field and looks decades older than her thirty years. Still when she sees Joan with the burlap bag on her head, a slight smile escapes from her wrinkled face.

JOAN'S MOTHER Ah! The little lady comes clothed for the feast of St. Agnes, while her mother is left to herd goats! Joan jumps off of the ladder. Realizes that she is still wearing the sack. Pulls it over her head, throws it on the ladder, grabs a stool and joins her mother. Now that the door is closed to keep in the goats, the only light comes from a window above Joan's mother, giving the barn the look of a dungeon. After a pause in which we take in the mud, the manure, the desolateness of the place, Joan breaks the silence:

JOAN Mother, was I born under the devil's own star?

JOAN'S MOTHER No. It was a black night that you were born. Who told you that?

JOAN He did. When I dropped his cheese and the fat pig Toto gobbled it up. Joan's mother stops milking the goat and looks uncertainly at her daughter then says hesitantly:

JOAN'S MOTHER The wind was from the north that night the home of Satan and his evil spirits. Your father took that badly. He says that's where you got your yellow hair and greenish eyes. Joan looks up in a sort of excited horror then whispers: JOAN Then I am Satan's own daughter. I'll end up in the Boar's Head Inn with the thieves and loose women!

JOAN'S MOTHER No. No my odd little Joan. It's true that the devil tempts you more than others. But you were baptized in the grand cathedral by Christ's own priest and the bells rang out for hours in all directions to chase away all evil and God's grace is stronger than the devil's north wind. Joan doesn't look convinced. As she considers this new information which would seem to explain her many problems, tears streak down her dirty face.

JOAN'S MOTHER Come, then. Enough nonsense. Tomorrow is the feast of St. Denis. The duke himself will be at the cathedral to dub the fine young knights. We'll finish our chores and then I'll wash your hair so clean that it will shine brighter than the church's golden spire. And let God decide if your eyes be the green of the devil or as blue as the robe of his own Virgin mother. A smile breaks through Joan's tears and she expertly grabs a goat and begins to milk it. Her mother begins to sing a sweet ballad and Joan happily joins in.

3. INT. DAY; DAWN , THE ENTRANCE TO THE BARN.

JOAN'S MOTHER (voice off) Hurry,Joan, the procession is passing!

JOAN Go ahead, I'll catch you in a minute! It's very dark in the barn. We just barely see Joan descending from the hayloft with a book in her arms. Amidst the braying of the goats we hear a dog barking. The big, shaggy sheep dog approaches Joan and wags its tail like a puppy. Joan pets it, then puts down her book to remove the heavy iron collar that is clamped tightly around its neck. JOAN That's a good dog Bilbo. It's the feast of St. Denis. You needn't work today! JOAN'S FATHER (voice off from a distance) Jo anne! Cursed girl! Get a move on or be eaten by wolves! Joan, picks up the book, rushes to the door, sticks the book in the bottom of a basket of food, and rushes through the door, slamming it behind her. As she runs toward the procession in the distance, we see Bilbo stick his nose through the slightly open barn door.

4. EXTERIOR DAY; EARLY SUNDAY MORNING (AUTUMN); THE ROAD TO YORK.

As the sun is rising, we hear the sound of voices singing and from a distance we see a long procession of peasants walking in twos and threes on the narrow dirt road that cuts through the nearly perfect squares of fields: oats, wheat, and rye readyfor the harvest. The people are in their Sunday bestÑinstead of the usual drab and dirty garments the girls are wearing clean light-colored or white dresses with garlands of fall flowers in their hair. Even Joan's father has washed his face and hands and he's walking proudly beside his wife in front of his brood of children. Joan is at the edge of the family, carrying a basket of cheese, bread and sausage for the family's lunch. She lags behind to pick flowers which she tosses on top the basket. As her mother had promised Joan's hair shines a glorious gold and she wears a simple but very pretty white dress. Even her father is taken in by her innocent beauty and he impulsively picks her up by he waist and swings her about. As the camera sweeps through the crowd we hear them singing a popular ballad that's more ribald than religious. But after a few minutes their voices are mixed with the sound of bells ringing from the Cathedral. Soon the voices are totally drowned out by the bells and the procession takes on a solemn dignified tone as it reaches the city gates.

5. INT. DAY; SUNDAY MORNING; THE CATHEDRAL OF YORK.

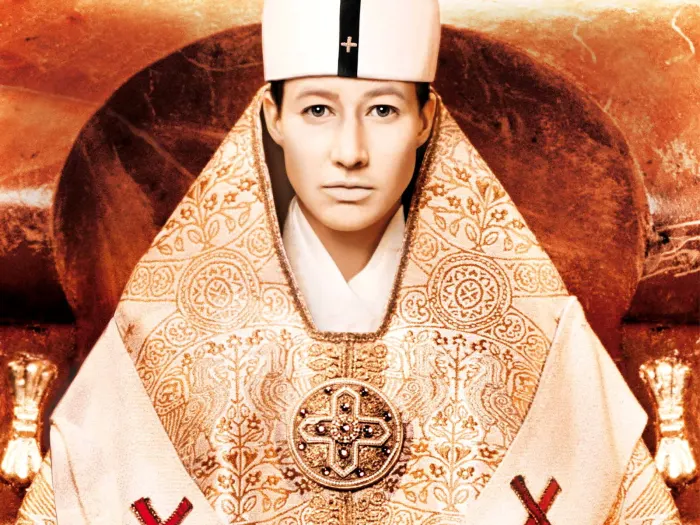

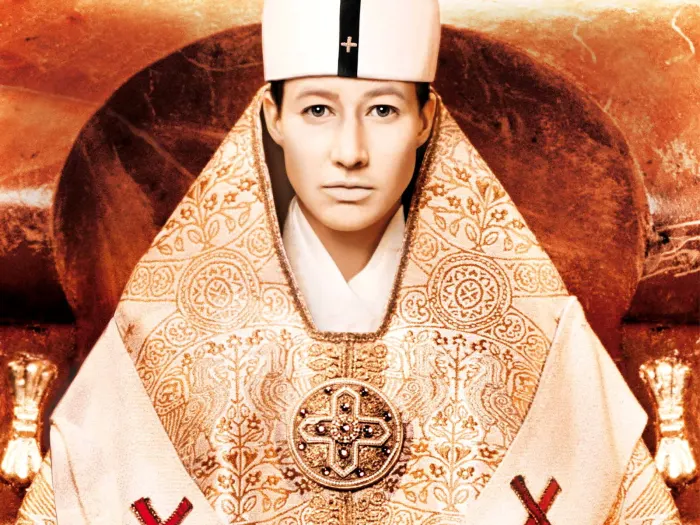

The cathedral is decked with tapestries on the walls and carpets on the front benches. Exquisite crucifixes, surrounded by images of the saints adorn the three altars. The whole cathedral blazes with light from the many-branched candelabras that glow on the rich vestments, the gold of the chalice, and the gleaming marble. The church is filled to the brim for the feast of St. Denis and the investiture of the nobles when the Bishop himself will celebrate mass and several young men will be dubbed knights by the Duke of York. The nobles strut up the center aisle in robes made of pheasant skins and silk, decorated with peacock feathers or purple and lemon colored ribbons. Some are draped round with ermine robes. They noisily take their places in the front rows. In sharp contrast are the delegation of Benedictine monks, who sit quietly to the side of the altar. Lastly the impatient peasants are seated in the back of the assembly. From them comes a polite murmur of awe at the richness of the altar and the clothing of the nobles. Amidst this murmur comes the sharp cry of a baby or a child being reprimanded. But the overall spirit is more of a festival than a religious service. Among the Benedictines we recognize the young handsome monk from the market. He is holding a bundle in his lap under his prayer book and is nervously eyeing the peasants as they arrive. Finally his gaze settles on Joan. Unlike the others she is kneeling perfectly still her eyes glued to the image of Christ in Majesty which hangs above the altar. The young monk is so taken by the vision of the girl with her now-golden hair that his neighborhas to nudge him to stand up for the singing of the first hymn. The monks begin to sing a hymn in Latin: When the singing begins Joan's gaze goes from the image of Christ to the congregation of monks. She searches the faces until her eyes stop on that of the young monk. When he looks up from his songbook, their eyes meet and they both smile. She slips her hand into the basket and pulls out the book from beneath the food and flowers. He flashes a big smile then holds up the bundle of cheese. After a moment's hesitation he points to side altar not far from where he sits. Joan nods in agreement. At this moment we see the astounded face of Joan's father and realize that he has followed at least part of their exchange. The mass progresses. The gospel is from the Apocalypse and rouses terror among the now-silent peasants. The sermon has to do with the hierarchy of Christ's familyÑthe message being that each man has his place and should stay in it. After the mass, with great pomp and ceremony, the nobles profess their oath to the duke, then after the duke and the bishop they parade out of the church. The monks follow and then the peasants rush into the aisle. In the confusion, Joan manages to slip away to the side altar. She doesn't see her father follow. He hides behind a pillar and listens as she pulls the book from the basket and hands it to the monk.

YOUNG MONK Ah! My St. Mark. I feared to never see it again! JOAN You left it by the tree. I wrapped it carefully in a cloth and wiped my hands each time I touched a page. Will I be cursed?

YOUNG MONK Whatever for?

JOAN My father says that books are magic and full of curses and evil arts. YOUNG MONK Perhaps some books, but not the Bible nor the holy Gospels. They're full of goodness and point the way to understanding the mysteries of Our Lord. JOAN Are only priests and monks able to understandÑto understand the markings in a book? YOUNG MONK No. Some noble men and even ladies have that talent. Their books have jeweled fronts and golden letters. . . And curses gainst girl with dirty hands. JOAN Then a girl can learn to read a book? YOUNG MONK If that be her place in life, indeed. But if her rightful place is with her goats, or in a field planting grain to feed her family, her bishop and her lord, she has no place for books and reading. Her destiny lies with her family. Your heard the bishop's sermon on that matter. JOAN But if I could read I could be holy and wise, like you. I could fight the devil's curse that blows on me with the north wind. The curse that gave me devil's eyes and yellow hair. And I could know why kings, and queens walked barefoot the to the visit the Baby Jesus when they surely owned the finest sandals. Joan's father sees that he is nearly alone in the deserted church and slips out through a side door. The monk passes Joan the bundle of cheese and turns to go.

YOUNG MONK Go now, and take this in reparation for the damage done by Toto. And rid your pretty head of books and talk of magic. God gave you sparkling eyes and golden hair to someday please a man and be a loving wife. You'll be wise to do your chores and obey your honest father till that day comes. Now, be gone, before he misses you.

6. EXT. DAY; SUNDAY NOON; THE PLAZA IN FRONT OF THE CATHEDRAL OF YORK.

There is much dancing, singing and merrymaking going on among both peasants and nobles. Tumblers, fools and jesters perform for the crowd while the newly dubbed knights prance around on horseback. In the confusion, Joan struggles to find her family and when she

does her brothers and sisters surround her and beg for lunch from her basket. But first she approaches her father and solemnly presents him with the cheese. JOAN It's from the monk in reparation for the damage done by his pet pig.

JOAN'S FATHER (raising his arm threateningly) Reparation, she says! He's given you more than cheese! Putting words into your head and books into your hands that are not fit for a simple girl. I say he be the devil's own messenger. He is too pretty of a boy to be a man of God!

JOAN'S MOTHER (soothingly) Please leave the girl in peace. She means no harm.

JOAN'S FATHER (lowering his arm) No good will come of this. (giving a menacing look to the rest of the children) Well, eat your bread, then, we'll not be staying here. There's animals to tend before the black night creeps in.

7. EXT., DUSK; ON THE ROAD AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE FARM.

Joan's family is slowly making its way back to the farm. It's turned cold and the night is falling fast. The sadness and weary attitude is in sharp contrast to the gaiety of the morning's procession. Joan is walking some twenty feet in front of the others and is the first to come upon a stray goat that is limping painfully.

JOAN Baby Moon! What's happened? You're bleeding! Her hoof is bleeding! Joan's father is at her side now, examining the bleeding goat.

JOAN'S FATHER The wolves have come. . . He grabs Joan by the hair and drags her to the barn door which is swinging open. The entrance is littered with the remains of several goats and a ram. In the middle of them lies Bilbo, without his protective collar his throat has been bitten open by a wolf. The ox is nowhere to be seen.

JOAN'S FATHER I'm ruined. Ruined by the work of Satan himself. I'll have no more of his daughter's curse upon my farm! Still holding Joan by the hair he grabs a hatchet twists her hair into a rope, places her head on a chopping block and swiftly cuts off her shock of golden hair. Holding the hair in one hand, he drags the girl back outside and into the hut that serves as their home. The whole family trails silently behind him. The embers of a fire are still burning on the hearth. He throws the hair onto it and grabs a hot poker.

JOAN'S FATHER The yellow hair has joined its maker. Now to be done with the green devil's eyes! He is about to strike her in the face with the red-hot poker when her mother comes between them, grabbing the hot iron with her bare hand.

JOAN'S MOTHER Stop! In heaven's name, she's but a girl. Burn the yellow hair, but leave her eyes alone. If she be taken by the devil let the priest defend us, but spare me my daughter's innocent eyes. He lets go of Joan and throws down the poker. Joan throws herself against her mother's pregnant womb. The other children stand back, not daring to make a move.

JOAN'S FATHER No priests will walk in my home. This be the work of priests and monks and magic books. So let her keep her evil eyes but let them never gaze on me or mine

again! Joan's mother gently pushes her toward the door. Joan is clinging to her and her mother has difficulty untangling herself. She whispers in Joan's ear.

JOAN'S MOTHER Peace, peace, my pretty one. Hide in the barn tonight. Sleep and time will calm your father's anger. But go now. Go up the ladder and hide yourself well from wolves and foxes. May God protect you, daughter. She manages to push Joan through the door, then pull it shut. Joan's father sits watching the hair sizzle on the hearth and moans to his wife:

JOAN'S FATHER The devil's curse lies on this house. I had six goats

that gave us milk and cheese. I had an ox that cut the work of plowing fields in two. I had two solid sons that could have helped me through this harvest. Why did the Lord see fit to take them with the pox and leave behind but babies and that cursed girl? Why did he send a wolf to take the only wealth I knew? What sin have I committed to deserve such trials? Joan's mother tries to console him:

JOAN'S MOTHER You've other sons that soon will be of age to help you in the fields and there's one more on the way. We'll save to buy another ox and goats. Till then give the girl a chance. Who knowswhat God intends for her. It's not for us to interfere with the workings of our Lord. Joan's father lets his head fall in his wife's lap. At the same moment the plait of hair bursts into flames on the hearth.

8. EXT; NIGHT; IN FRONT OF THE HUT.

Joan is now outside alone. The moon is full and she has no problem finding her way back to barn. She enters. Fastens the door behind her. Steps over the dead animals and starts to climb up the ladder to the loft when she sees Baby Moon, nudging its dead mother. She tears a strip of material from her now-ragged dress and makes a bandage for the

goat's leg. Then, with some difficulty, Joan climbs the ladder to the loft with the animal in her arms. She backs into a corner, covers herself and Baby Moon with the bag that had served as her monk's robe and silently shivers.

9. INT; DAWN; THE HUT.

It is still quite dark outside as Joan gently pushes open the door to her family's home. In the faint morning light we can vaguely see a big wooden bed in which her father, mother and two or three small children are sleeping under a duvet. Her father is snoring loudly. Joan creeps past the bed and over to a low wooden chest which sits against the opposite wall. She slowly opens it and fumbles through the contents, pulling out a pair of leggings and a short jerkin that had belonged to one of her older brothers. She then slips back out of the hut.

10. EXT.; DAWN; BEHIND THE HUT.

Joan has put on her dead brother's clothes and with her short cropped hair, she could easily pass for a boy. She stands by the pond and studies her

reflection. In the water we see her vague boyish figure, the baby goat at her side. Joan recites to herself as if a prayer or ritual: JOAN This be the work of priests and monks and magic books. I'll never lay my evil eyes on him or his again! She throws her dirty white dress in the water, considers her shoes for a moment, then throws them into the water as well. She then picks up her basket which holds a slice of bread and a round of cheese and walks to the road. Baby Moon follows her.

JOAN Be gone, Baby Moon. You'll come to no good on my heels. I have no home nor any milk to give you. But the little goat continues to follow her down the road towards York.

11. EXTERIOR DAY; ATERNOON; THE ROAD TO YORK.

Joan is walking very slowly along the edge of a field towards the cathedral in the distance. Her bare feet are bleeding from the rough ground and she can barely go on. She's carrying the little goat in her arms.

JOAN Poor little Baby Moon. I told you not to come. That everyone I gazed on would be cursed. A gray-haired, bearded monk wearing a long black robe approaches in a wagon from behind her. He takes in the state of her feet and stops beside her.

ALCUIN Good morning, my son! Joan, forgetting she is dressed as a boy ignores the greeting and continues walking, her eyes to the ground.

ALCUIN (a bit irritated) Hey! I say good morning, my son! Joan looks up now realizing that her disguise has worked, but quickly looks away.

JOAN Good morning father! ALCUIN And where be you going with bare feet and a baby goat, my son?

JOAN To the monastery, father.

ALCUIN That falls well, since I am going there myself. Perhaps I could offer you a ride. But why do you look always at the ground, my son? JOAN Because of the curse, good father. I've got the devil's eyes.

ALCUIN And how is that? JOAN They're evil green and bring bad luck to everyone they look on.

ALCUIN Look at me son! (Joan looks up) You see I do not tremble. I do not fall. Who told you such nonsense?

JOAN My father did. And it's true because of me he lost six goats, his ox, and Bilbo the dog. She pauses, then adds in explanation. I was born in the devil's North wind.

ALCUIN Evil eyes and evil winds! A lot of midwives' tales. Jump up here, son, I'm not afraid of pagan superstitions.

JOAN Then you must have a book like the white monk did.

ALCUIN What monk is this? JOAN I met him at the market. He wears a robe like yours but white. And his hair is long and black and his face is smooth, not covered with hair like yours.

ALCUIN Now let me guess. Black hair, young, white robe. Did he happen to have a pig at his feet?

JOAN He was carrying one! TotoÑa white pig that ate my cheese and started all my troubles!

ALCUIN Ah, I knew that no good would come from that overfed pig. We'll roast him this Christmas. Come up here then. Joan places the goat in the back of the wagon. Then accepts the hand of the old monk and jumps up beside him. ALCUIN Thomas would have a book with him. Heis one of our finest scribes.

JOAN Thomas?

ALCUIN Yes, like the Apostle who doubted our Lord. My name is Alcuin, I watch over the scriptorium. And what are you called, my boy? JOAN Jo. . . John. My name is John and my goat is Baby Moon. She was born with the shape of the moon stamped on her back. What's a scriptorium? ALCUIN The workshop where we copy precious books. We're sure to find Thomas there. But tell me, son, what leads you to our monastery?

JOAN Destiny. It's written in the magic books, but to know my destiny I must first learn to understand the markings.

ALCUIN But what of your father, doesn't he need a fine strong lad like you to help him in the fields?

JOAN I have no father. He banished me from the farm as God did Eve and Adam from the garden. ALCUIN Because of your evil eyes?

JOAN Yes. He tried to burn them out. Alcuin looks at her gently and motions for her to lie down beside him. Lay down your head, my boy. Your eyes have seen enough for this afternoon. Close them now and sleep. We'll soon be home.

12. EXTERIOR DAY; AFTERNOON; THE ROAD TO THE MONASTERY.

Crossing the endless moors of Yorkshire, the one-horse cart of Alcuin slowly makes its way east towards the sea. Joan is still stretched out sleeping with her head in Alcuin's lap.

13. EXTERIOR DAY; DUSK; THE ROAD TO THE MONASTERY.

Alcuin has now reached the hills just before the coast. He stops the cart on top of a promontory and we see the ancient monastery on the seacoast in the distance. Joan, who has never before seen the sea, wakes up and rubs her eyes in disbelief.

JOAN What trick is the devil playing on me now? I believe I see a lake that has no shoreÑor a river that's burst God's natural banks. Which is it good father? ALCUIN (laughing) Neither one nor the other. That's the North Sea, my son. JOAN Does it touch the end of the world?

ALCUIN Oh, no! Beyond it lies the land of the infidelsÑthe yellow-haired Northmen who sometimes cross the sea in great sailing ships which fly on the North wind. They bring with them fire and destruction. JOAN (whispering) Like Satan himself. ALCUIN Like Satan himself. Joan moves closer to Alcuin and hides her face in his cloak as the old monk urges the horse to continue to the monastery.

14. EXTERIOR NIGHT; WHITBY ABBEY. Alcuin and Joan finally arrive in front of the great gates of the abbey. Joan has once again fallen into a deep sleep and after handing the horse and cart and Baby Moon over to the stable boy, Alcuin picks her up, carries her to the infirmary and pounds on the door. Gregory, the physician and a jolly, well-fed monk, who had been sleeping in a corner of the room, awakens and lights an oil lamp.

GREGORY Who is that, pounding at my door after Compline has passed? Be you devil or friend?

ALCUIN For the moment it is Alcuin your friend. But I will raise the devil if you do not open at once! Gregory opens the door and Alcuin stumbles in with his heavy bundle, which he throws on the bed. Joan awakens and looks around at the spotless infirmary and its four beds with white linen. She takes in the mysterious jars of herbs lined up on shelves along the wall, then the row of leather-bound books. Finally her eyes rest on an elaborately-jeweled crucifix.

JOAN Have I died then, like the dog Bilbo? Am I in the room that leads to heaven?

ALCUIN You are quite alive, my boy, although some would claim you have reached the antechamber of Paradise. Gregory pushes Alcuin away and gently grasps one of Joan's bleeding and swollen feet.

GREGORY You've brought me a pretty boy, indeed, but what penance brought this on? Build up the fire, dear Alcuin. We'll need to heat some water to wash the wounds. But you, boy, what caused this? Have you no shoes? JOAN I walked the better part of the dayÑbarefoot like the kings in the white monk's book. But I believe they journeyed on a path of smooth gold stones while I tramped through the stubby fields of oats and rye. GREGORY (smiling) I see, I see. The white monk's book. Gregory motions for Joan to stay seated on the edge of the bed and moves over to the fireplace where Alcuin has built up the fire and hung a pot of water above the flames.

GREGORY (whispering) The white monk?

ALCUIN He means Thomas. The young novice who spends all his days hunched over his desk in the scriptorium. It seems that the boy's father has sent him here to study with Thomas.

GREGORY (as he fills a basin with the warm water) That's odd. It's past the season for accepting young scholars. Is he then related to the novice Thomas?

ALCUIN (hesitantly) Perhaps. Or possibly Abbot Edward agreed to take the lad in exchange for some service rendered to the abbey. At any rate, I should inform him of the boy's arrival.

GREGORY Can we not wait till dawn to wake the Abbot; Enough of God's good sleep has been lost for one night. . . Go instead to the kitchen and bring us a loaf of bread. You and the boy must be famished after so long a trip. Alcuin goes off to the kitchen as Gregory gently washes Joan's feet. He then puts the basin aside and pours three glasses of spiced red wine from a glass decanter which he takes from among the bottles of herbs. He hands a glass to Joan.

GREGORY Here, drink this. It will bring color to your cheeks. JOAN (sipping the wine, then touching her cheeks) And are they red then, like the drink? GREGORY (touching her cheek) A rose is blooming there. Continue drinkingÑsoon your cheeks will be as red as autumn apples. As Joan continues to sip the wine, Alcuin returns with the bread. He divides it into three parts and raises his glass to those of Gregory and Joan.

ALCUIN To the health of our newest scholar! He then hands a piece of bread to Joan.

JOAN (suddenly worried, sets down her glass) I am not fit to eat the fine white bread and drink the spiced wine of monks and lords. Have you no scraps of rye bread and a cup of water for me?

GREGORY (sternly) We'll let the Abbot determine what you are fit for tomorrow. But tonight you are my guest and must eat and drink as I do. And you'll not catch me drinking water! Joan, her doubts put to rest, now gobbles down the bread and finishes the wine. Her face is flushed and once again taken by fatigue, she lies back on the bed, her eyes barely open. Alcuin slips away, leaving Gregory alone with the child.

GREGORY (gently wrapping a bandage around Joan's foot) So you thought to walk on a carpet of gold, like the images in a holy book! For that you deserve to stay with me tonight. We'll find your white monk in the morning. But sleep now. It will soon be the hour of Matins. Gregory finishes wrapping a bandage around Joan's foot, pulls a blanket up over her, kisses her on the forehead and puts out the light.

15. INT. DAYBREAK; INFIRMARY; WHITBY ABBEY.

Joan is still sleeping in the infirmary bed as Thomas enters, angrily banging the door behind him. He approaches the bed with the intention to scold the peasant boy for using his name as a wayof spending the night in the monastery, but when he sees Joan's angelic face still deep in sleep his attitude changes and a smile creeps over his face.

THOMAS (whispering) So this is the peasant boywho would be my cousin John. Joan is more likely the case. The girl from the cathedral without her golden locks. I'll find her breakfast and send her on her way before she's found out. Joan awakes and smiles at Thomas.

THOMAS Good morning, cousin John!

JOAN (rubbing her eyes) Ah, it's you! But why do you call me cousin? And where is your is pig? And where is my goat Baby Moon?

THOMAS My pig is out rolling in his morning mud bath. Your goat is lapping up a bowl of milk in the stable. And I call you cousin because the learned Alcuin seems to have taken you for that. What lies have you forced his honest ears to hear?

JOAN No lies at all. I told him of my evil eyes, the devil and my coming from the north wind. I never called you cousin, but I may have called you friend. Was I mistaken?

THOMAS Of course you were mistaken! It is not fit for a Benedictine novice to be the friend of a runaway girl. Now put on your shoes and be off with you! Joan throws back the sheets of the bed, puts her feet on the ground and tries to stand.

JOAN I have no shoes. I threw them to the devil to fill his hungry belly . And I have no home because of the devil's curse that brought the wolf and killed my father's dog, six goats, and possibly the ox. My father chopped away the awful yellow hair and promises to burn my evil eyes if I go back. My only hope lies in the secrets of your magic books.

THOMAS (suddenly worried) But you can't stay here! You're a girl! It's impossible to keep a secret within these walls. You'll be found out within the day and I'll be called to count for it! Thomas is interrupted by Gregory entering with a bowl of milk, a loaf of bread, and a bundle of clothes. He sets his load down on the table, lifts Joan up off of the floor, and lowers her back on the bed.

GREGORY Off your feet, my son. You'll have plenty of time to follow your cousin to the scriptorium. Today, you must rest and prepare for the Abbot's visit. I've brought you a tunic and tights fit for a young scholar. But perhaps we should bathe you first. I'll heat up water for the tub. JOAN Oh no! I've just had a bath on Saturday. Not even the Abbot could ask for more. GREGORY So you don't like to bathe. Yet you must know the importance of cleanliness for a monkÑthe body is the tabernacle of the soul . . .But never mind we'll wash your hands and face. Here put these on. Gregory passes Joan the clean tights and tunic. She moves to the other side of the bed and, turning her back to the monks, puts on her new clothes. She then climbs back into the bed and Gregory hands her the bread and

milk.

GREGORY Well be off to the chapel then, Thomas. And stop to see the cellarer for a bed mat. There are no free beds in the scholars' dormitory, so John will be lodging with you for the time being.

THOMAS But perhaps I should first speak with the Abbot. I believe there has been a . . . misunderstanding.

GREGORY Misunderstanding? No. It is quite correct that you share your cell with your young cousin. You're still a novice, Thomas. You've not yet taken final vows and are free to communicate with others. Especially a close member of your family. Get going now or we will both be late for Prime. Thomas stumbles confusedly through the door as Joan eats her breakfast under the smiling regard of Gregory.

16. INT. AFTERNOON ; SCRIPTORIUM; WHITBY ABBEY.

Several monks are seated at

their desks, each positioned under a window of the scriptorium. They are busy either illuminating books or copying texts. Alcuin is walking among them observing and giving advice. Joan is seated in the corner on a high stool at a desk next to Thomas. Her bare feet are twisted and tense as she carefully dips her quill pen into the inkhorn. Light floods in from the window above her and we see her copying the text from the very book of Gospels that Thomas had first left with her at the market. She is working so intensely that she seems to be in a trance. When she finally notices Alcuinstudying her, Joan quickly changes her attitude to that of a light-hearted student. Her tensed shoulders loosen up and her feet swing freely.

JOAN Give me a riddle to solve, Brother Alcuin.

ALCUIN Ah, if my young friend insists. Here is one I once posed to Charlemagne's son Pippin when I tutored him at Court: I have seen the dead create the living and the dead consumed by the breath of the. living. How is this?

JOAN (after a short pause) From the rubbing together of sticks which are dead fire is born which is living and consumes them. Alcuin pats Joan on the head and laughs. Then looks her seriously in the eye. You're a tough one to catch up, mon ami. With your quick wit and bright eyes. You're different from the other boys. There's some secret you guard closely in your heart. Can you not share it with your friend?

JOAN And if knowing his secret meant losing your friend? Would you still insist to ask?

ALCUIN A friendship built on lies will consume itself like the sticks in their fire. . . but enough of riddles, recite to me your grammar for today. Thomas shoots a troubled look at Alcuin, then Joan as she begins to expertly recite a lesson from her Latin grammar.

17.TEN YEARS LATER, SUMMER (800) INT. MORNING; CHAPEL; WHITBY ABBEY.

Joan is now eighteen years old and is being initiated into the community of adult monks. She kneels facing the altar, still dressedin the white unhooded robe of a novice, and reads aloud her personal written pledge of commitment:

JOAN My Lord God I humbly beseech thee to accept me as thy servant in the blessings of thy sweet meekness, so that I may deserve to come worthily and devoutly into this holy brotherhood. Stir my heart and loose it from the dull heaviness of my mortal body. Let me partake in the mysteries which pass the subtlety of angels. She lays down the paper and bows further down, her forehead nearly touching the step of the altar, then continues her pledge reciting by heart. I hereby renounce the pleasures of the flesh in embracing the vow of chastity; the vanities of the earth through the sweet promise of poverty; and the treachery of pride in submitting my body and mind to the will of the most worthy Abbot Edward. Joan signs the document and places it on the altar. Then in the manner of a prince dubbing a young knight, Abbot Edward places a cowled robe on Joan's back, makes the sign of the cross, and gives her the kiss of peace. Wrapping herself in the robe Joan now stands and turns around and we see her face. It is both ascetic and noble, simple yet graced with a troubling beauty. The brothers now walk by her and each one kisses her on both cheeks. When Thomas arrives, he holds her slightly longer than the others and a warm smile of friendship passes between them. The abbot then takes her by the arm and leads the new monk to the door of the church.

ABBOT EDWARD Go now in peace, Brother John, and profit well of your retreat. For these three days contemplate the weight that you have taken on. Consider your vows and speak not a word nor remove your cowl, neither by day nor by night. Let your robe be as a cocoon within which you will change from man to monk In this inner cloister you will be as Christ was in the tomb and on the third day you will come back into our brotherhood transformed and reborn. Joan leaves the chapel and goes toward her cell a the monks begin to chant in the background. She walks, not with the hunched scholar's shoulders that afflict most of the other monks, but with a proud, queenly grace.

18. THREE DAYS LATER, SUMMER(800) EXT. MORNING; THE GARDEN OF WHITBY ABBEY.

Joan and Thomas are walking along the garden path. It's a fresh June morning and several monks are planting and working the soil. Joan kicks off her

sandals, picks them up, then stops to pluck a rose. JOAN Did you know that roses can cure anger?

THOMAS (smiling) Anger. How is that?

JOAN You pluck a rose and a bit of sage and grind them to a powder. Then the moment you feel anger swelling within you, place the powder before your nose and inhale deeply. The sage appeases anger and the rose brings joy in its stead.

THOMAS Who taught you that, a midwife from your childhood?

JOAN No, Brother Gregory. He knows remedies for all that afflicts us. A bit of hemlock will make you sleep. Although too much will act as a poison. Fennel will

make you jolly and sweet-smelling. And to calm an improper desire a monk need only cook the leaves of the endive plant and place them on his loins during a hot bath. THOMAS Brother Gregory told youthat? JOAN No that I learned from a midwife! Joan stops and picks up a handful of earth and smells it with the same enthusiasm she had shown for the rose.

JOAN Three days cooped up in my cell. I believe I missed the smell of the earth more than the sound of a human voice.

THOMAS More than you missed me?

JOAN The earth smells of my childhood, my mother, my baby goat. You wear the scent of books and ink and a winter passed in the scriptorium.

THOMAS Ah, then, your love of books has lost its flame. Three days of solitude and the longings of a peasant girl return. JOAN Can I not love the books of the scriptorium and the pleasures of the earth?

THOMAS No. No more than be a woman and a monk at one and the same time. Joan quickly looks around, sees that they are alone, then answers.

JOAN For that, I have renounced my womanhood.

THOMAS Perhaps in the scriptorium, where your mind is master. But here in nature you wear it like Eve. (Turning serious) How could you take the vows? How could you go so far as to make a mockery of our holy vows?

JOAN I never made a mockery. I took the vows as you did. I am as much a monk as you. And I will cherish my chastity till the Apocalypse comes. Can you say the same?

THOMAS Yes, I would like to believe so, but I feel we've done some evil thing against God. Against nature. It was different when you first followed me here. You were just

a frightened child. And I was both foolish and . . .

JOAN And what? THOMAS Perhaps proud of your attention, perhaps in love.

JOAN As a brother?

THOMAS That is what I told myself. JOAN And now?

THOMAS Now I live in torment. Three days without your eyes, your smile, your voice. The scriptorium was like a tomb. My conscience says the only way to save our souls is to separate our bodies. I should insist that you leave here and join a proper women's convent. And yet my heart refuses. JOAN (holding him in her arms) I would leave here if I could, Thomas. To spare you any suffering. But I cannot go to a convent. My destiny does not lie shut up in a cloister amongst women. God sent you to fetch me from my family and bring me here. If he wanted me to be a nun he would have sent a shriveled up old abbess.

THOMAS (smiling and gently pushing her away) Your logic would never get past Alcuin. But on one point I agree. You belong in the world not in a cloister. (looking away) Sometimes I imagine you in a bridal bed with only your long golden hair to cover your white breasts and myself free to . . .

JOAN (grabbing his hand) You have to pray, Thomas. All men face the same temptation of the flesh. All monks must pass this trial. Our love is pure and true. Don't let the devil tempt you with sensual images as he did Christ in the desert. Think rather of Christ's pure love for Mary Magdalene. He lived and preached with her. If he could resist such great beauty, you can certainly fight off a passion for a plain little mouse like me. Thomas takes her tightly in his arms now and whispers. THOMAS My sister, brother, lover, friend. How could I ever learn to live without your roses and your smiles? The church bells begin ringing and the couple separates and hurriedly retrace their steps.

19. INT. LATE AFTERNOON ; AUGUST; SCRIPTORIUM; WHITBY ABBEY.

Joan and Thomas are alone in the scriptorium. The windows are open behind the half-closed shutters and we hear the sound of birds singing and the young scholars playing in the courtyard. The air is heavy and hot and Joan's black robe is barely resting on her shoulders over her thin linen smock. Her golden hair which isstill cut in a short page boy is curling from the heat and makes her look more feminine than the last scene. Thomas is illuminating a text with red foliage, while Joan is copying a Latin poem from Ovid. She stops in order to tease Thomas by translating and reciting a passage in English.

JOAN (hesitantly) The air was burning and the day had passed the half of its course; I rested my limbs inthe middle of the bed.

THOMAS (interrupting, pretending to be stern) We are permitted to copy Ovid in order to study the Latin grammarÑwe need not concern ourselves with meaning.

JOAN (continuing asif she had not heard) One shutter was open, the other closed and the light was like that of the forestÑthat half-day that reigns when Phebus has fled, or when it is no longer night but not yet morning. It was the sort of light necessary to overcome the modesty of frightened girls . . .

THOMAS (becoming upset) Please stop. What you are saying is sinful. You have no right to enjoy suggestive pagan texts. Stop now or you will find yourself in confession. JOAN (Still teasing, like a schoolgirl, she lets her robe fall to the ground) Corrine entered, veiled only by a thin, floating tunic, her hair falling on either side of her white neck . . . Thomas jerks his brush and an ugly smudge of red paint covers the delicate figure that he had been designing in the margin of a text. He looks up and sees Joan dressed in only her linen smock, the curves of her young body showing through. Trembling he grabs her robe and throws it over her. THOMAS Your father was right. You are the devil's daughter! How can you flaunt your womanhood so when you know how much I suffer?

JOAN (frightened by his anger, holding her robe tightly at the neck) I'm sorry. I meant no harm. Just to be funny like when we were young. Since I took my vows, you've been so, so. . . serious and . . . distant.

THOMAS And what if another monk should enter? Would that be amusing to you? Your shame? Our shame?

JOAN But we are the only ones exempt from the afternoon service. The others will all be in the chapel for at least another hour. And even if someone did approach we would hear him in the passageway.

THOMAS And we were dispensed from our prayers so that we might finish urgent workÑnot to translate pagan texts and flaunt our vows of chastity.

JOAN (beginning to understand the seriousness of her action) I never meant to tempt our vows of chastity. The air was heavy, I let my robe fall from the heat. THOMAS You were seduced by the words of the licentious Ovid. Alcuin should never have put such a book into the hands of a weak woman.

JOAN Me, weak! You're the one who trembled like a boy!

THOMAS Like a man, rather. I am a man you know. I've seen twenty-six springs.

JOAN (mocking) Perhaps you should try a bath with endive. He looks at the smudged manuscript and, moaning lays down his head. Joan approaches and touches his shoulder.

JOAN (gently) I'm sorry. I get so impatient with this heat. It makes me say unjust words. Joan tries to massage his shoulders, but Thomas pushes her away.

THOMAS No, please, go. I need to be alone to meditate. To overcome this desire. You're right. It is I that trembled. And continue to do so. Please go. And cover your hairÑeven disguised as a boy you trouble the virtue of the other monks. I've seen them coveting you. With angry tears forming in her eyes, Joan quickly lifts up her cowl and hiding within it rushes from the scriptorium.

20. AUGUST, EXT. LATE AFTERNOON; CAVES ABOVE THE SEACOAST.

Joan and Alcuin are unloading books from the back of a donkey and placing them at the entrance to a cave. Taking a break from the work, Joan looks out over the calm water. JOAN Do you think that the Northmen would really attack this haven of peace?

ALCUIN (continuing to unload the books) They've already landed further north on the coast. And they've sacked every monastery in Northumberland. JOAN But what do they want with us? ALCUIN They want gold, mon ami! The gold of the chalices, the jewels of reliquaries, the treasure of the abbey ..

JOAN But the scriptorium, the library? What interest have they in our books? ALCUIN None at all, but old books make an impressive bonfire.

JOAN Sometimes I believe they're coming because of my sins. ALCUIN (jokingly) What sin could you have on your heart that deserves such a heavy payment? Yourgravest faults are that you refuse to wear shoes or to bathe in the presence of others; even the physician Gregory. . . Joan self-consciously draws her robe closer, and looks down at her bare feet, but says nothing. Alcuin raises her chin and tries to make her look at him.

ALCUIN I am your confessor, John, what you tell me will reach no other ears. Joan looks at him now and in a halting voiceasks:

JOAN Will you hear my confession now, father?

ALCUIN Yes, but let's go inside. I think I must sit awhile. He motions for her to enter the cave and follows. Alcuin sits on a rock and Joan kneels on the dirt floor at his side.

ALCUIN Bare your soul, my son. God will forgive you. JOAN Do you remember when I first came here? ALCUIN (smiling) Yes, barefoot with a baby goat at your heels.

JOAN And with the devil's curse from the North WindÑthe same wind that brings the ravenous Northmen. I came here to conquer that curse but instead I simply covered it up, disguised it in monk's clothing.

ALCUIN Enough of curses and evil winds, my boy, whatever have you done to bring on the wrath of the Northmen?

JOAN I've tempted Thomas by reading from Ovid. ALCUIN Your cousin Thomas?

JOAN He's not my cousin.

ALCUIN Then what is he?

JOAN My friend. Yet he would be more.

ALCUIN Ah, now you speak of deceit and unnatural love.

JOAN Deceit yes. But not unnatural love.

ALCUIN Yet a love that is

more than that of brothers should be?

JOAN Yes, but not unnatural.

ALCUIN There you pose me a fine riddle, mon ami. How can two handsome young monks love each other as more than brothers should and not go against the laws of nature? JOAN You see, I was just a gg. . . a child. . . and I thought that if I put on the clothes of a scholar, then a novice . . . and if I studied and thought like a monk, I could change myself, change the skin that God put me in. I've always believed that God wanted me to do so. That that's why he sent the wolves . . . or why he allowed Satan to send the wolves. But I've failed his test and proved to be the devil's own child. And now he is coming for me.

ALCUIN (growing impatient) If you wish to confess and obtain Our Lord's forgiveness you must stop speaking in riddles. A stifled rumble, like faraway thunder can be heard coming from the seacoast. Both Alcuin and Joan emerge from the cave and look down on the coastline to see what the droning canbe. They see a long line of what look like enormous red-shelled turtles winding up the path toward them. JOAN My confession brings a sea a blood and monsters that would drown us in it.

ALCUIN Monsters yes. But mere men carrying their blood-red shields on their backs. We've no time to waste. Hurry back to the abbey and warn the abbot. Tell him to send the monks to hide in the

forestÑespecially the young ones. The Northmen will attack in the night.

JOAN Come with me. They're sure to find you. The trail passes by here and they'll see the donkey's prints that lead to the cave.

ALCUIN No. I'll hide the books, close the cave, and then I will go to meet them. JOAN (astonished) Go to meet them? Alcuin takes hold of the donkey and removes a last bundle from the beast's back. He opens it for Joan to see.

JOAN Gold!

ALCUIN The abbey's fortune. I thought to hide it, but it will be of better use to buy our freedom. JOAN They would accept a ransom? ALCUIN They might.

Northmen often do. At any rate they may leave me in peace. It's the young men they want. Young enough to be sold as slaves.

JOAN Thomas . . .

ALCUIN Yes, Thomas and the others. Hurry, and warn them. Run, you'll go faster on foot and perhaps they'll trade my life for the ass. Joan starts to run then turns back and shouts: JOAN And my confession? Can you absolve me, father?

ALCUIN (sadly) When theinfidels have passed, mon ami, until then I'll consider your riddle. Go now. . . He enters the cave. Joan hesitates a moment, then rushes down the hill toward the abbey.

21. DUSK, CHAPEL; WHITBYABBEY.

The monks are gathered in the chapel chanting Vespers when Joan rushes in and whispers to the Abbot. He motions for the singing to stop.

ABBOT The moment we have feared has come, my brothers. The Northmen have arrived. Brother Alcuin will try to buy their clemency, but even gold may not calm their famous thirst for blood. So let all those of able body take with them sustenance for three days and nights and what they can carry of our holy books and relics and be off into the woods. Stay there till a signal be given and God protect you. As for those who prefer to stay with me, let us busy ourselves with hiding what we may. The Abbot blesses them and there is a general rush to grab relics and golden chalices. As the young monks leave the chapel, the others gather what cannot be carried away and hide it under the altar. They then join the Abbot in prayer. Joan stands stunned in the midst of the chaos until Thomas takes her hand.

THOMAS The books. The scriptorium. We must save what we can. Joan wakes up as if from a trance and follows Thomas out of the chapel as the older monks begin to chant in vigil.

22. INT. DUSK ; SCRIPTORIUM; WHITBY ABBEY.

Joan and Thomas are in

the library of the scriptorium with a few other monks. Joan has already the Gospels of St. Mark, which she has cherished since her childhood. Thomas is wrapping up a bundle of fragile manuscripts. Joan hesitates at a bookshelf.

JOAN And how does one choose between Boethius and St. Augustine?

THOMAS Whichever is lighter. Joan tries to shove both books into her already full pilgrim's satchel. Thomas angrily throws one of the books to the ground.

THOMAS We must go now. No book is worth your life! Joan acts as if she would argue this point but Thomas takes her hand and drags her out of the scriptorium.

23. EXT., NIGHTFALL; COURTYARD; WHITBY ABBEY.

Night is falling fast and in the last light the monks are packing their bags. Some have horses or donkeys, others are leaving on foot. Brother Gregory is at the kitchen door passing out bundles of provisions. He gives Thomas his package.

GREGORY Take this Thomas and protect your young cousin. Heaven forbid that he should fall into the hands of the heathens. Gregory then hands Joan her package and kisses her on the cheek.

JOAN Come with us, Brother Gregory.

GREGORY No, I've too many years and too many pounds to carry with me. I would only be a hindrance. And besides I might still be of use here. Let God's will be done . . . Gregory presses a bottle of wine into Joan's hand and Thomas urges her on. They follow a steady line of monks flowing out the great gates of the abbey and into the neighboring forest.

24. EXT., NIGHT; FOREST

Joan and Thomas are huddled together under a rough shelter in the forest. In the distancethe sky above the monastery is bright with the light of flames.

25. EXT., MORNING; COURTYARD; WHITBY ABBEY.

Billowing smoke can be seen as Joan and Thomas approach the abbey. When they enter the courtyard the principal buildings have burned down and the fire is still smoldering in the ruins. Only the chapel, the infirmary and part of the scriptorium remain standing. The door to the chapel has been knocked down and Joan and Thomas must climb over it to enter. Once inside they are met with an atrocious sight. A pool of blood comes running down the center aisle from the main altar that has been overturned to remove the hidden treasure. The monks who had stayed behind have been hacked down with hatchets and heavy swords as if they were animals. Their bodies are heaped in a pile at the foot of the altar. Joan approaches and picks up an abandoned hatchet, which closely resembles the one her father had used on her so many years earlier.

THOMAS God forgive them . . .

JOAN (throwing down the bloody hatchet) There is no God here. There is only Satan . . .

26. INT., MORNING; INFIRMARY; WHITBY ABBEY.

Brother Gregory is huddled in the corner of the infirmary, amidst broken bottles and overturned beds. He's wearing a crown of woven weeds around his head, clutching a half-empty bottle of wine in his hand and talking to himself in a delirium. Joan and Thomas make their way to him through the shambles.

GREGORY My life for a barrel of wine. I drank with them. I danced for them. With the devil's own army. The young monks each take an arm and try to lift Gregory from

the floor. But he resists and they are helpless against his weight.

GREGORY My life for a barrel of wine. Afraid to die in the name of Our Lord. I gave them the key to the cellar. I drank with them. I danced for them. With the devil's own army. JOAN Brother Gregory, have you seen Alcuin? Did he manage to escape? Joan shakes Gregory by the shoulder but he is lost in his own world. He holds up the

bottle as if to toast her.

GREGORY My life for a barrel of wine! Here's to the devil's own army! Joan gives up and follows Thomas back out into the courtyard.

27. INT., AFTERNOON; SCRIPTORIUM; WHITBYABBEY.

The scriptorium has been ransacked; bookcases are overturned, manuscripts are torn to pieces, ink has been splashed over everything. Joan and Thomas pick through the piles of books to see what can be saved. Thomas comes across the book of Ovid's poems that had caused them so much distress just a week earlier. He flips through the pages until he finds the poem that Joan had translated. He

begins to read aloud:

THOMAS (sadly) The air was burning and the day had passed the half of its course; I rested my limbs in the middle of the bed.. . .

JOAN So now even the chaste Thomas reads sinful pagan texts.

THOMAS (skimming a bit then going on) Corrine entered, veiled only by a thin, floating tunic, her hair falling on either side of her white neck . . . JOAN And what of the vows

that would bind you till the Apocalypse comes?

THOMAS (looking up from the text) Look around you. The words of the prophets from their holy booksÑspit upon, walked upon, pissed upon . . . The bodies of the holiest of holy butchered at God's altar like so many fat cows. . . Is this not the Apocalypse? You were right when you said there is no God here. He has deserted this place. . . Thomas looks down at the book again and continues to read aloud: I grabbed the tunic ; the slightest obstacle, but she would stay veiled by it. After fighting like one who did not wish to win, she let herself be conquered with no regrets. Then she stood before me, unveiled, and her nude body was without fault. What arms! What shoulders! And her breasts that married perfectly the form of my hand! and that flat stomach under a perfect bust! those hips fine and full! those thighs tingling with youth! But why go into details?Everything I saw was magnificent and I held her naked against myself. .